A closer look at the MC4R pathway

The melanocortin-4 receptor (MC4R) pathway plays a critical role in maintaining a healthy body weight.

Signaling along this pathway regulates hunger, satiety, and energy expenditure, all of which can influence body weight.9,10

Explore the impact of the MC4R Pathway in Bardet-Biedl syndrome (BBS)

Functional pathway signaling

The MC4R pathway plays a key role in regulating hunger, which involves neural activation within the hypothalamic region of the brain in response to leptin release from adipose tissue. Proper regulation of hunger requires sufficient levels of melanocyte-stimulating hormone (MSH) neuropeptides that activate MC4R, triggering a reduction in hunger and concomitant increase in energy expenditure.1,11-15

Impaired pathway signaling

Distinct from general obesity cases, rare genetic diseases of obesity can be non-syndromic (e.g., POMC or LEPR deficiency) or syndromic (e.g., Bardet-Biedl syndrome or Alström syndrome).

The role of genetic variants

Genetic testing can help reveal disease-causing genetic variants. The American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics classifies variants into 5 categories, as follows:16-19

Pathogenic

Likely Pathogenic

Variant of Uncertain Significance (VUS)

Benign*

Likely Benign*

*often reported as negative

- Benign and likely benign variants are generally not included in a diagnostic report

- If a VUS is identified, efforts by the testing laboratory may be taken to resolve the classification as pathogenic or benign as new information becomes available20

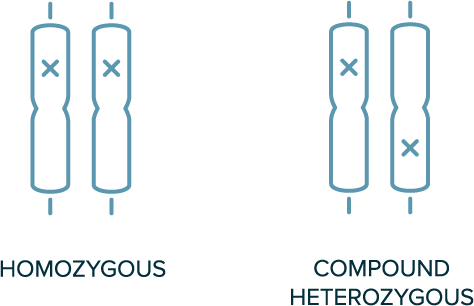

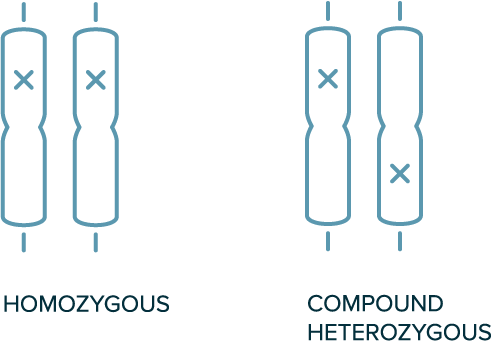

Patterns of inheritance21

Rare genetic diseases of obesity are inherited in several patterns, depending on the gene involved and whether the related genotype is dominant or recessive.

In autosomal recessive inheritance

- 2 copies of variant allele are required for the phenotype to be present (e.g., homozygous or compound heterozygous variants are required)

- Both parents of the affected individual are likely carriers of a single variant

- Not typically observed in every generation

Biallelic Genotypes

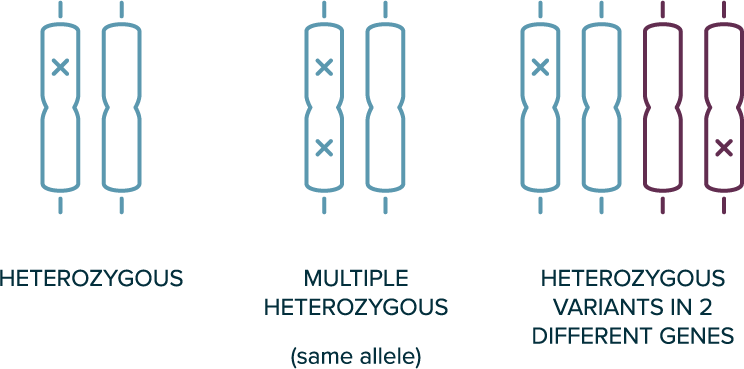

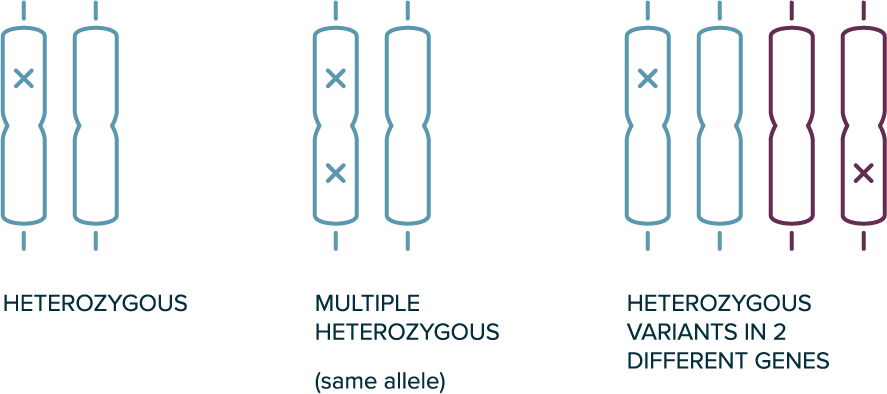

In autosomal dominant inheritance

- 1 copy of the allele is sufficient for the phenotype to be present (e.g., heterozygous variants are sufficient)

- The affected individual likely has 1 affected parent

- Disease can occur in every generation

Heterozygous Genotypes

Rhythm Pharmaceuticals offers a no-charge genetic testing program for rare genetic diseases of obesity. The genes and chromosome region included in the test are listed below and are also available here.

Gene or region symbols may change and are current as of October 2024.

| Gene Symbol or Region (alternate*) | OMIM Gene Number |

|---|---|

| ADCY3 | 600291 |

| AFF4 | 604417 |

| ALMS1 | 606844 |

| ARL6 (BBS3) | 608845 |

| ASIP | 600201 |

| BBIP1 (BBS18) | 613605 |

| BBS10 | 610148 |

| BBS12 | 610683 |

| BBS1 | 209901 |

| BBS2 | 606151 |

| BBS4 | 600374 |

| BBS5 | 603650 |

| BBS7 | 607590 |

| BBS9 (PTHB1) | 607968 |

| BDNF | 113505 |

| CFAP418 (BBS21) | 614477 |

| CEP164 | 614848 |

| CEP290 (BBS14) | 610142 |

| CPE | 114855 |

| CREBBP | 600140 |

| CUL4B | 300304 |

| DNMT3A | 602769 |

| DYRK1B | 604556 |

| EP300 | 602700 |

| GNAS | 139320 |

| HTR2C | 312861 |

| IFT172 (BBS20) | 607386 |

| IFT27 (BBS19) | 615870 |

| IFT74 (BBS22) | 608040 |

| INPP5E | 613037 |

| Gene Symbol or Region (alternate*) | OMIM Gene Number |

|---|---|

| ISL1 | 600366 |

| KIDINS220 | 615759 |

| KSR2 | 610737 |

| LEP | 164160 |

| LEPR | 601007 |

| LRRC45 | |

| LZTFL1 (BBS17) | 606568 |

| MAGEL2 | 605283 |

| MC3R | 155540 |

| MC4R | 155541 |

| MECP2 | 300005 |

| MKKS (BBS6) | 604896 |

| MKS1 (BBS13) | 609883 |

| MRAP2 | 615410 |

| NCOA1 (SRC1) | 602691 |

| NPHP1 | 607100 |

| NR0B2 | 604630 |

| NRP1 | 602069 |

| NRP2 | 602070 |

| NTRK2 | 600456 |

| PCNT | 605925 |

| PCSK1 | 162150 |

| PHF6 | 300414 |

| PHIP | 612870 |

| PLXNA1 | 601055 |

| PLXNA2 | 601054 |

| PLXNA3 | 300022 |

| PLXNA4 | 604280 |

| POMC | 176830 |

| PPARG | 601487 |

| Gene Symbol or Region (alternate*) | OMIM Gene Number |

|---|---|

| PROK2 | 607002 |

| RAB23 | 606144 |

| RAI1 | 607642 |

| RPGRIP1L | 610937 |

| RPS6KA3 | 300075 |

| SCAPER | 611611 |

| SCLT1 | 611399 |

| SDCCAG8 (BBS16) | 613524 |

| SEMA3A | 603961 |

| SEMA3B | 601281 |

| SEMA3C | 602645 |

| SEMA3D | 609907 |

| SEMA3E | 608166 |

| SEMA3F | 601124 |

| SEMA3G | |

| SH2B1 | 608937 |

| SIM1 | 603128 |

| TBX3 | 601621 |

| TMEM67 | 609884 |

| TRIM32 (BBS11) | 602290 |

| TRPC5 | 300334 |

| TTC8 (BBS8) | 608132 |

| TTC21B | 612014 |

| TUB | 601197 |

| UCP3 | 602044 |

| VPS13B | 607817 |

| WDPCP (BBS15) | 613580 |

| 16p11.2 chromosomal region† | 611913‡ |

*Alternate gene symbols or phenotype abbreviations listed for clarity.

†Assessment for rearrangement of the 16p11.2 chromosomal region.

‡OMIM phenotype number.

Gene symbols and alternative names may change and are current as of October 2024.

ALMS1=Alström syndrome 1; LEPR=leptin receptor; PCSK1=proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 1; POMC=proopiomelanocortin; SH2B1=SH2B adaptor protein 1; SRC1=steroid receptor coactivator-1.

-

References

-

Huvenne H, Duberne B, Clément K, Poitou C. Rare genetic forms of obesity: clinical approach and current treatments in 2016. Obes Facts. 2016;9(3):158-173.

-

Ellacott KL, Cone RD. The role of the central melanocortin system in the regulation of food intake and energy homeostasis: lessons from mouse models. Philos Trans R Soc Land B Biol Sci. 2006;361(1471):1265-1274.

-

Hales CM, Fryar CD, Carroll MD, Freedman DS, Ogden CL. Trends in obesity and severe obesity prevalence in US youth and adults by sex and age,

2007-2008 to 2015-2016. JAMA. 2018;319(16):1723-1725. -

Sherafat-Kazemzadeh R, Ivey L, Kahn SR, et al. Hyperphagia among patients with Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Pediatr Obes. 2013;8(5):e64-e67.

-

Ward ZJ, Long MW, Resch SC, Giles CM, Cradock AL, Gortmaker SL. Simulation of growth trajectories of childhood obesity into adulthood. N Engl J Med.

2017;377(22):2145-2153. -

Data on file. Rhythm Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Boston, MA.

-

Styne DM, Arslanian SA, Connor EL, et al. Pediatric obesity-assessment, treatment, and prevention: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin

Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(3);709-757. -

Cuda S, Censani M, O’Hara V, et al. Pediatric Obesity Algorithm eBook. Obesity Medicine Association. 2020-2022.

http://www.obesitymedicine.org/childhood-obesity. Accessed June 8, 2021. -

Morton GJ, Meek TH, Schwartz MW. Neurobiology of food intake in health and disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2014;15(6):367-378.

-

van der Klaauw AA, Farooqi IS. The hunger genes: pathways to obesity. Cell. 2015;161(1):119-132.

-

da Fonseca ACP, Mastronardi C, Johar A, Arcos-Burgos M, Paz-Filho G. Genetics of non-syndromic childhood obesity and the use of high-throughput DNA sequencing technologies. J Diabetes Complications. 2017;31(10):1549-1561.

-

Yazdi FT, Clee SM, Meyre D. Obesity genetics in mouse and human: back and forth, and back again. PeerJ. 2015;3:e856.

-

Burns B, Schmidt K, Williams SR, Kim S, Girirajan S, Elsea SH. Rai1 haploinsufficiency causes reduced Bdnf expression resulting in hyperphagia, obesity and altered fat distribution in mice and humans with no evidence of metabolic syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19(20):4026-4042.

-

Lu Q, Yang Y, Jia S, et al. SRC1 deficiency in hypothalamic arcuate nucleus increases appetite and body weight. J Mol Endocrinol. 2018:JME-18-0075.R2.

-

Vaisse C, Reiter JF, Berbari NF. Cilia and obesity. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2017;9(7):a028217.

-

Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17:405-424.

-

Sequencing Sample Reports: Indeterminate (with CNV). Prevention Genetics. Updated October 18, 2009. https://www.preventiongenetics.com/ClinicalTesting/TestCategory/sampleReports. Accessed November 11, 2021.

-

A guide to understanding variant classification. Blueprint Genetics. https://blueprintgenetics.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Variant_Classification_WP_VARA41-06-FINAL.pdf. Accessed November 11, 2021

-

VUS – the most maligned result in genetic testing. Blueprint Genetics. Updated October 29, 2020. https://blueprintgenetics.com/resources/vus-the-most-maligned-result-in-genetic-testing/. Accessed November 11, 2021.

-

Bean LJH, Tinker SW, da Silva C, Hegde MR. Free the data: one laboratory’s approach to knowledge-based genomic variants classification and preparation for EMR integration of genomic data. Hum Mutat. 2013;34:1183-1188.

-

Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man. Entries 609734, 600955, and 614963. https://www.omim.org/. Accessed November 18, 2021.

-

Kohlsdorf K, Nunziata A, Funcke JB, et al. Early childhood BMI trajectories in monogenic obesity due to leptin, leptin receptor, and melanocortin 4 receptor deficiency. Int J Obes (Lond). 2018;42(9):1602-1609.

-

Heymsfield SB, Avena NM, Baier L, et al. Hyperphagia: current concepts and future directions proceedings of the 2nd international conference on hyperphagia. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2014;22 Suppl 1(0 1):S1-S17.

-

Shah BP, Moeller IH, Van der Ploeg LHT, Garfield AS. Identification and functional characterization of novel variants in genes in the MC4R pathway associated with severe early-onset obesity and hyperphagia. Oral presentation at: Keystone Symposia. February 2019. Banff, Alberta, Canada.

-

Rhythm 10-K Annual Report (2020). Rhythm Pharmaceuticals. Accessed November 11, 2021.

-

Rhythm 10-K Annual Report (2024). Rhythm Pharmaceuticals. Accessed March 15, 2024.

-

Ayers KL, Glicksberg BS, Garfield AS, et al. Melanocortin 4 Receptor pathway dysfunction in obesity: patient stratification aimed at MC4R agonist treatment. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103:2601-2612.

-

Forsythe E, Kenny J, Bacchelli C, Beales PL. Managing Bardet-Biedl syndrome—now and in the future. Front Pediatr. 2018;6:23.

-

Forsythe E, Beales PL. Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet. 2013;21(1):8-13.

-

Pigeyre M, Yazdi FT, Kaur Y, Meyre D. Recent progress in genetics, epigenetics and metagenomics unveils the pathophysiology of human obesity. Clin Sci (Lond). 2016;130(12):943-986.

-

Joy T, Cao H, Black G, et al. Alström syndrome (OMIM 203800): a case report and literature review. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:49.

-

Van Groenendael S, Giacovazzi L, Davison F, et al. High quality, patient centred and coordinated care for Alstrom syndrome: a model of care for an ultra-rare disease. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2015;10:149.

-

Waters AM, Beales PL. Ciliopathies: an expanding disease spectrum. Pediatr Nephrol. 2011;26:1039.

-

Paisey RB, Steeds R, Barrett T, et al. Alström Syndrome. GeneReviews®. February 7, 2003. Updated June 13, 2019. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1267/. Accessed November 10, 2021.

-

Coll AP, Farooqi SI, Challis BG, Yeo GSH, O’Rahilly S. Proopiomelanocortin and energy balance: insights from human and murine genetics. J Clin Endocrinal Metab. 2004,89:2557.

-

Mendiratta MS, Yang Y, Balazs AE, et al. Early onset obesity and adrenal insufficiency associated with a homozygous POMC mutation. Int J Pediatr Endocrinal. 2011;5.

-

National Institutes of Health. POMC deficiency. MedlinePlus®. Updated August 18, 2020. https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/condition/proopiomelanocortin-deficiency/. Accessed November 10, 2021.

-

Farooqi IS, Wangensteen T, Collins S, et al. Clinical and molecular genetic spectrum of congenital deficiency of the leptin receptor. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:237.

-

Stijnen P, Ramos-Molina B, O’Rahilly S, et al. PCSK1 mutations and human endocrinopathies: from obesity to gastrointestinal disorder. Endocr Rev. 2016;37(4):347-371.

-

Martin MG, Lindberg I, Solorzano-Vargas RS, et al. Congenital proprotein convertase 1/3 deficiency causes malabsorptive diarrhea and other endocrinopathies in a pediatric cohort. Gastroenterology. 2013;145(1):138-148.

-

Rui L. SH2B1 regulation of energy balance, body weight, and glucose metabolism. World J Diabetes. 2014;5:511.

-

Doche ME, Bochukova EG, Su HW, et al. Human SH2B1 mutations are associated with maladaptive behaviors and obesity. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:4732.

-

Yang Y, van der Klaauw AA, Zhu L, et al. Steroid receptor coactivator-1 modulates the function of Pomc neurons and energy homeostasis. Nat Commun. 2019;10:1718.

-

Cacciottolo TM, Perikari A, van der Klaauw A, et al. Rare variants in Steroid Receptor Coactivator-1 (SRC-1) associated with obesity, adipose tissue dysfunction and liver fibrosis. QJM. 2019;112(9);724-729.

-

National Institutes of Health. Bardet-Biedl syndrome. MedlinePlus®. Updated August 18, 2020. https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/condition/bardet-biedl-syndrome/#inheritance. Accessed June 15, 2021.

-

Pomeroy J, Krentz AD, Richardson JG, et al. Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Pediatr Obes. 2021;16:e12703.

-

Forsythe E, Sparks K, Hoskins BE, et al. Genetic predictors of cardiovascular morbidity in Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Clin Genet. 2015;87(4):343-349.

-

Vos N, Oussaada S, Cooiman MI, et al. Bariatric surgery for monogenic non-syndromic and syndromic obesity disorder. Curr Diab Rep. 2020;20(44):1-10.

-

Kenny J, Forsythe E, Beales P, Bacchelli C. Toward personalized medicine in Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Per Med. 2017;14(5):447-456.

-

Poitou C, Mosbah H, Clement K. Mechanisms in endocrinology: update on treatments for patients with genetic obesity. Eur J Endocrinol. 2020;183(5):R149-R166.

-

Srivastava G, Apovian CM. Current pharmacotherapy for obesity. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2018;14(1):12-24.

-

Beales PL, Elcioglu N, Woolf AS, Parker D, Flinter FA. New criteria for improved diagnosis of Bardet-Biedl syndrome: results of a population survey. J Med Genet. 1999;36(6):437-446.

-

Forsyth R, Gunay-Aygun M. Bardet-Biedl syndrome overview. GeneReviews®. July 14, 2003. Updated July 23, 2020. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1363/. Accessed November 10, 2021.

-

Alvarez-Satta M, Castro-Sanchez C, Valverde D. Alström syndrome: current perspectives. Appl Clin Genet. 2015;8:171-179.

-

Nordang GBN, Busk OL, Tveten K, et al. Next-generation sequencing of the monogenic obesity genes LEP, LEPR, MC4R, PCSK1 and POMC in a Norwegian cohort of patients with morbid obesity and normal weight controls. Mol Genet Metab. 2017;121:51.

-

Aliferis K, Helle S, Gyapay G, et al. Differentiating Alström from Bardet-Biedl syndrome (BBS) using systemic ciliopathy genes sequencing. Ophthalmic Genet. 2012;33(1): 18-22.

-

Eneli I, Xu J, Webster M, et al. Tracing the effect of the melanocortin-4 receptor pathway in obesity: study design and methodology of the TEMPO registry. Appl Clin Genet. 2019;12:87-93.

-

Seo S, Guo DF, Bugge K, Morgan DA, Rahmouni K, Sheffield VC. Requirement of Bardet-Biedl syndrome proteins for leptin receptor signaling. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18(7):1323-1331.

-

Courbage S, Poitou S, Le Beyec – Le Bihan J, et al. Implication of heterozygous variants in genes of the leptin-melanocortin pathway in severe obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106(10):2991-3006.

-